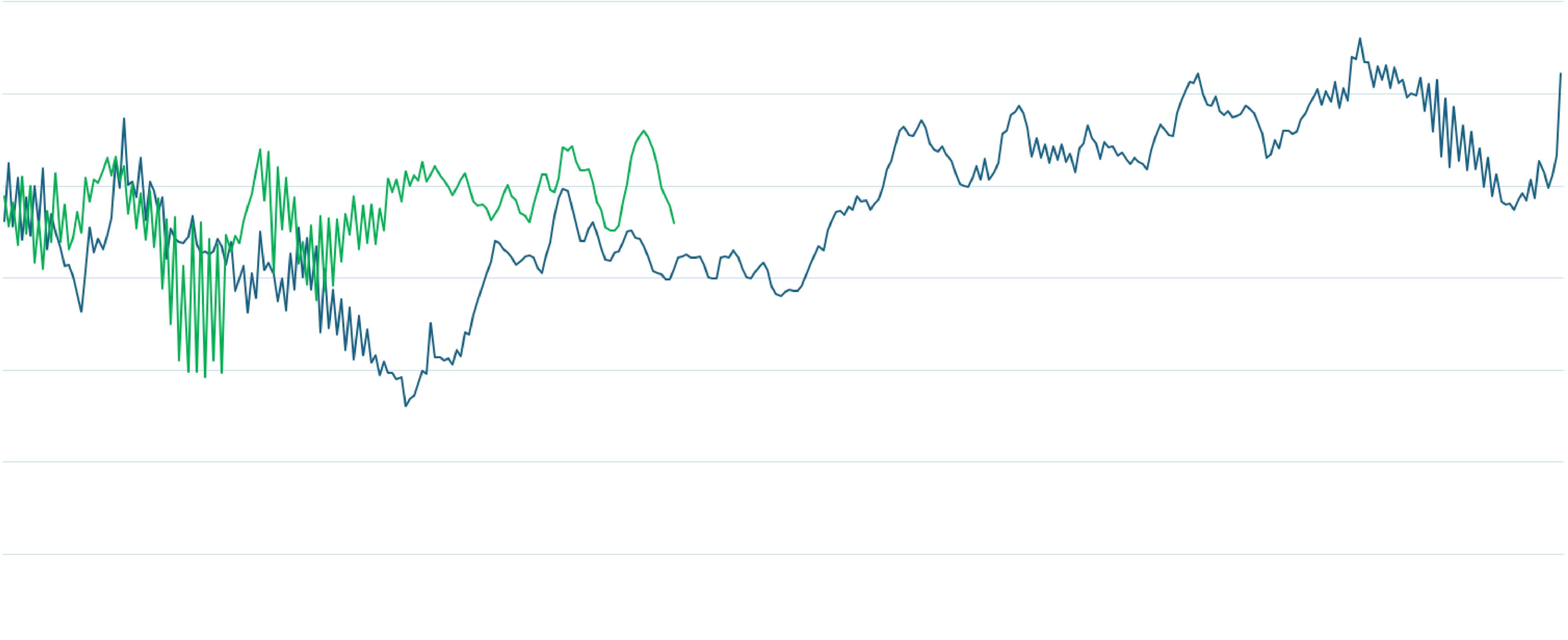

The past three seasons have painted three vastly different financial pictures for New Zealand dairy farmers – from extraordinary highs to challenging lows.

This season everyone strapped themselves in for sustained turbulence. However, there are now signs that the industry could get above the cloud cover and be able to find some smoother flying if the pilots of those operations adjusted to the conditions well enough – and early enough. Having a plan and being detailed appears to be at the heart of this conversation.

The 2020-21 season was positive with the three main profit drivers – FWE (farm working expenses), EBITD/ha (expenses before interest, tax and depreciation) and the milk price – all playing well together. In 2021-22 the milk price was a belter – and it was the glue that held everything else together, even though it came with tax consequences.

By 2022-23, the winds had changed and rising interest rates (from 4% to 7.9% in 2021-22, then from 7.5% to 10% in 2022-23) and costs had a mid-air collision with falling milk prices and started to shake things up.

The current season is the first where farmers have had to deal with sustained higher interest rates all season, together with a milk price that began from $6.75/kg of milk solids (MS). The silver lining – if there has been one – has been the easing of some farm costs.

So how is everyone holding up?

MilkMaP’s Senior Farm Business Consultant, Andrew Trounce, says thriving in today’s volatile farming climate is a complicated conversation.

MilkMaP Consulting focuses on “milk”, “management” and “profitability”, by analysing its clients’ cost structures, and the impact of any proposed feeding or stocking-rate changes.

Its senior consultants have been tracking their clients’ results – throughout the country – for several seasons now. Its 2022-23 end of year (EOY) summaries, include comparisons on all the main income and cost categories, the data breakdowns, the costs, and profit (per hectare, per cow, and per kilogram of MS).

The reports are visual and numerical, and show correlations between key performance criteria, including the two main profit drivers – FWE (farm working expenses), and EBITD/ha (expenses before interest, tax and depreciation).

Andrew says there are producers who are successfully navigating the bumpiest ride they’ve been on in the past decade by using attention to detail and their key professionals.

He says in the main, their clients had handled the 2022-23 season’s instability well, which included fertiliser costs rising by 16%, administration costs jumping by 21%, and vehicle expenses lifting by 16% (driven by fuel costs).

“It’s been very volatile with a lot of movement within a year, and if you looked at the 10 years prior to that things were reasonably static,” Andrew says.

“Normally you talk about that with a sense of the milk price, but not so much when it comes to the operating spend.”

PRODUCTION HELD TO 1% DROP

Production per hectare did drop marginally for the third consecutive year – pressed by external factors, such as falling stocking rates (down 3.5% or 0.15 cows/ha), nitrogen limits, consent-to-farm regulations, and a cold 2022 spring. However, the end-of-season effort held the impact of those collective factors to an overall average fall for MilkMaP’s clients of just 1% in kilograms of MS/ha.

“If we looked at the 2022 spring we were dealt, we couldn’t do much about getting to that peak milk because pasture is still 80-90% of the cows’ diets, so if they were having to deal with poorer quality silage, they’d still find it very hard to mitigate those impacts completely,” Andrew says.

“But from Christmas 2022 onwards, the decline from peak milk was able to be managed well to minimise the damage. The result was down 4kg of MS/cow. That’s pretty good compared to what it could have been. Our clients essentially held that number to what we would usually describe as a general movement from one year to the next.

“Add that to the climate through autumn, winter, and this spring, and nature played ball pretty well.

“We haven’t had to deal with 100+mm of rainfall, snow or any other major events during that time. That’s allowed the cows to put weight on, hold production at the end of the season, get through winter relatively unscathed, and come into this spring in really good nick. It has set up this season to help minimise costs, and to do reasonably good milk.”

- 2020-21

- FWE/kg of MS lifted 2.5%

- EBITD/ha lifted 13%

- Milk price lifted 6.3%

- 2021-22

- FWE/kg of MS lifted 18.3%

- EBITD/ha lifted 21.3%

- Milk price lifted 22.9%

- 2022-23

- FWE/kg of MS lifted 7.08%

- EBITD/ha down 18.9%

- Milk price down 6.56%

PROFITABILITY TESTED BY INTEREST AND COSTS

The final numbers coming out of the 2022-23 season were starting to show the strain of higher interest rates and costs, and Andrew confirms that profitability per hectare largely returned to 2020-21 levels.

“The problem with that is that three years ago the finance cost was half of where it is today – and that’s the other part of the story,” he says. “What was dropping out the bottom was at the same level, but you’ve now got double the spend with interest, while income hasn’t lifted proportionately.

“When everything within the key profit drivers is going in the same direction, it’s okay, but when the milk price started to turn downwards that’s when the crunch came.

“A big point is that the overall operating costs of our clients went up 7%.”

But he says some of the costs that make up that spend – such as feed costs – rose only 4.4%/kg MS.

“What I mean by that is that if I looked at the total feed-cost category in the 2021-2022 year, it made up 22.9% of the total spend, but in this year just finished [2023] it dropped back to 22.4%.

“That shows that the other operating costs were rising at a faster rate than what the feed costs were.

“One of the big moving parts was the cost of nitrogen, which was $1300 a tonne.

“Now, we are looking at $899 a tonne. That is one of the areas that have massively reduced in costs this season. The fertiliser price has also come down and is now in line with the milk price.”

FARMERS HELD THE LINE

Andrew says he couldn’t fault how their clients responded to the pressure.

“Farmers had a good handle on the boots-on-the-ground stuff – decisions about what to spend money on and what not to. If you looked at this last year, guys didn’t necessarily reduce feed when the feed costs went sky-high, which allowed them to hold production later in the season. It shows the importance of getting the milk production to dilute their costs.”

He says that’s not to say there hasn’t been a lot of fine management needed within that commentary to keep ahead of the pain rolling into this season.

“It has come down to attention to detail. Some of our clients have condition scored their herds and perhaps pulled the bottom 10% of lighter cows out and milked them once-a-day [OAD] if need be, which also potentially helped with conception on those cows. Those kinds of decisions have yielded a better result than putting the whole herd on OAD, for example.”

SEASON PRICE FINISH

Andrew says with the value of hindsight, the early warning on milk price hasn’t been all bad.

“That first indicator down to $6.75 was probably good timing because it meant that people were so early in their season, they were able to alter a few things here and there – and cut out some unnecessary spends – before it had already been spent.

“Who knows where it will end up, but despite the early signals that it was going to be a very tight year, as the season has gone on, the outlook seems to have improved.”

He says there are still things that can be done to ease things.

“It’s important to make sure what you’re doing – and how you’re doing it – is happening as well as it possibly can be. Because you can be extremely profitable in a System 3, 4 and 5. You don’t have to be one or the other – it really comes down to how well you run it.

“And, understanding your key profit drivers is critical, so you don’t reduce spends in areas where it will have a negative impact on production. In 2022-2023, 95% of our clients continued to feed grain in the same amounts when the prices were high, because they could see the value of it and they didn’t want to negatively impact production,” Andrew says.

“I will add that it’s important to note that different feeds have a different impact. For example, you can’t replace 1kg of grain with 1kg of Palm Kernel and expect the same result, just because it’s $20 or $30/tonne cheaper.

“And a lot of our guys have played the game this season where grain prices have been falling so, they have not forward contracted. They have waited and then bought on the spot market, which has worked well for them.”

FARMING IS NOW MORE COMPLEX

Andrew says it’s important that dairy farmers keep their fingers on the pulse when it comes to costs for the next two years, given that interest rates appear likely to linger and regulations aren’t easing off.

“What could have been a successful model in the past may not be a successful model moving forward, and that never goes away.”

Andrew says the work that MilkMaP is completing by tracking its clients’ results is showing that if cows are working close to (or at) their potential, it will lift production per hectare. That, in turn, means more milk from fewer cows, which creates a more efficient system because there will be less per-cow fixed costs.

In this subject matter, the K.I.S.S. theory [Keep It Simple, Stupid] doesn’t apply.

“In some business there is a need for some complexity to gain the level of performance you’re trying to achieve. Trying to simplify things with a broad brush over a bulk number of farms typically has a negative outcome for those high-performing farms.

“The take-home message I’m seeing is that by understanding your costs and knowing your key profit drivers [i.e., production/cow and therefore/ha] you can deliver the best level of profitability for your farm.

“And, unless you know the data, and you’re at the top of your game with the one-percenters and all those things that are attached to it, it can be very hard to keep ahead of everything.”